In

March of 2008, Debbie and I took a drive (11 hours and 2,050 miles)

south the Sevierville near the Great Smoky National Park for a week

vacation. In addition to visiting the park we also went to Chickamauga

National Battlefield in Georgia and Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga. On

our way home, we took a detour of I-81 to visit Greeneville, Tennessee

and visit the home of our 17th president, Andrew Johnson. After touring

his home (both his first and second) along with the museum in the

Visitor Center we drove to the his grave in Andrew Johnson National Cemetery.

Johnson is a milestone for me becoming the 30th DPOTUS on my list.

In

March of 2008, Debbie and I took a drive (11 hours and 2,050 miles)

south the Sevierville near the Great Smoky National Park for a week

vacation. In addition to visiting the park we also went to Chickamauga

National Battlefield in Georgia and Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga. On

our way home, we took a detour of I-81 to visit Greeneville, Tennessee

and visit the home of our 17th president, Andrew Johnson. After touring

his home (both his first and second) along with the museum in the

Visitor Center we drove to the his grave in Andrew Johnson National Cemetery.

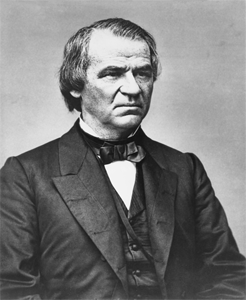

Johnson is a milestone for me becoming the 30th DPOTUS on my list.Johnson was a U.S. Senator from Tennessee, at the time of the secession of the Southern states. He was the only southern Senator not to quit his post upon secession and later was appointed military governor of Tennessee. Johnson became the Vice President in 1864 on the ticket with Lincoln. Johnson became president upon Lincoln's assassination on April 15, 1865. As president, he fought with the Radical Republicans in Congress and became the first U.S. President to be impeached.

Johnson, who was of Scots-Irish and English decent, was born in 1808, in Raleigh, North Carolina, to Jacob Johnson and Mary McDonough. Andrew Johnson's father died when Andrew was three years old, leaving his family in poverty. Johnson's mother then worked to support her family and later remarried. She bound Andrew as an apprentice tailor when he was 14 but at age 16-17 he and his brother ran away to Greeneville, Tennessee, where he found work as a tailor. Johnson married Eliza McCardle Johnson at the age of 19. He never attended any type of school and taught himself how to read and spell; his wife taught him arithmetic, and how to read and write more fluently.

Johnson, who loved to talk politics, used his tailor shop in Greeneville to start his political career. Johnson served as an alderman in Greeneville from 1829 to 1833 and was elected mayor of Greeneville in 1833. In 1835 he was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives, where after serving a single term he was defeated for re-election. In 1839 he was elected to the Tennessee Senate, where he served two two-year terms. In 1843 he became the first Democrat to win election as the U.S. Representative from Tennessee's 1st congressional district; he held the office for five terms. Here is a photo

President Andrew Johnson house. Johnson owned this home for 24 years,

both before and after his presidency. He lived here until is death in

1875, however, he did not die here.

Here is a photo

President Andrew Johnson house. Johnson owned this home for 24 years,

both before and after his presidency. He lived here until is death in

1875, however, he did not die here. During the Civil War the home was used by both Union and Confederate troops as headquarters. A section of the left on the walls by soldiers during that time has been left exposed for visitors to see. Some of the graffiti written by Confederate soldiers is not very complimentary of Johnson "the traitor".

Johnson was elected governor of Tennessee, serving from 1853 to 1857, and was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate and served from October 8, 1857, to March 4, 1862. Before Tennessee voted on secession, Johnson, who lived in Unionist east Tennessee, toured the state speaking in opposition to the act, which he said was unconstitutional. Johnson was an aggressive stump speaker and often responded to hecklers, even if those hecklers were in the senate. At the time of secession of the Confederacy , Johnson was the only Senator from the seceded states to continue participation in Congress. In March 1862, shortly after the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson and the capture of Nashville, Lincoln appointed Johnson military governor of Tennessee. During his three years in this office he "moved resolutely to eradicate all pro-Confederate influences in the state." This "unwavering commitment to the Union" was a significant factor in his choice as vice-president by Lincoln. According to tradition and local lore, on Aug. 8, 1863, Johnson freed his personal slaves. He vigorously suppressed the Confederates and later spoke out for black suffrage.

As a leading War Democrat and pro-Union southerner, Johnson was an ideal candidate for the Republicans in 1864 as they enlarged their base to include War Democrats and changed the party name to the National Union Party. He was elected Vice President of the United States. At the inauguration ceremony, Johnson, who had been drinking (he explained later) to offset the pain of typhoid fever, gave a rambling speech and appeared intoxicated to many. In early 1865, Johnson talked harshly of hanging traitors like Jefferson Davis, which endeared him to the Radicals.

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth while attending a play at Ford's Theater. Booth's plan included the assassination of Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward that same night. Seward narrowly survived his wounds, while Johnson escaped attack, when his would-be assassin, George Atzerodt, failed to go through with the plan.

Upon the

death of Lincoln the following morning, April 15, 1865, Johnson was

sworn in as President of the United States by Lincoln's newly appointed

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. He was the first Vice President to

succeed to the U.S. Presidency upon the assassination of a President

and the sixth vice president to become a president.

Upon the

death of Lincoln the following morning, April 15, 1865, Johnson was

sworn in as President of the United States by Lincoln's newly appointed

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. He was the first Vice President to

succeed to the U.S. Presidency upon the assassination of a President

and the sixth vice president to become a president.

Photo is of President Johnson's desk in his

home in Greenesville, Tennessee. The office is to the right of the

front door seen in the above photo.

As

president, Johnson forced the French out of Mexico

by sending a combat army to the border and issuing an ultimatum. The

French withdrew in 1867, and their puppet government quickly collapsed.

Secretary of State Seward negotiated the purchase of Alaska from the

Russia Empire on April 9, 1867, for $7.2 million. Critics sneered at "Seward's Folly" and "Seward's Icebox" and

"Icebergia."

However,

it was Post-Civil War Reconstruction that shaped Johnson's legacy. At

first Johnson talked harshly, "Treason must be made odious... traitors

must be punished

and impoverished ... their social power must be destroyed." But then he

struck another note: "I say, as to the leaders, punishment. I also say

leniency, reconciliation and amnesty to the thousands whom they have

misled and deceived."

His class-based resentment of the rich appeared in a May 1865 statement

to W. H. Holden, the man he appointed governor of North Carolina, "I

intend to confiscate the lands of these rich men whom I have excluded

from pardon by my proclamation, and divide the proceeds thereof among

the families of the wool hat boys, the Confederate soldiers, whom these

men forced into battle to protect their property in slaves. "Johnson

in practice was not at all harsh toward the Confederate leaders. He

allowed the Southern states to hold elections in 1865 in which

prominent ex-Confederates were elected to the U.S. Congress; however,

Congress did not seat them. Congress and Johnson argued in an

increasingly public way about Reconstruction

and the manner in which the Southern secessionist states would be

readmitted to the Union. Johnson favored a very quick restoration,

similar to the plan of leniency that Lincoln advocated before his death.

The Democratic Party, proclaiming itself the party of white men, north and South, aligned with Johnson. However the Republicans in Congress overrode his veto and the Civil Rights bill became law. The last moderate proposal was the Fourteenth Amendment, designed to put the key provisions of the Civil Rights Act into the Constitution, but it went much further. It extended citizenship to everyone born in the United States (except Indians on reservations). Johnson used his influence to block the amendment in the states, as three-fourths of the states were required for ratification. (The Amendment was later ratified.)

The

moderate effort to compromise with Johnson had failed and an

all-out political war broke out between the Republicans (both Radical

and moderate) on one side, and on the other Johnson and his allies in

the Democratic party in the North, and the conservative groupings in

the South. The decisive battle was the election

of 1866. Johnson campaigned vigorously but was widely ridiculed.

The Republicans won by a landslide (the Southern states were not

allowed to vote), and took full control of Reconstruction. Johnson was

almost powerless.

The

moderate effort to compromise with Johnson had failed and an

all-out political war broke out between the Republicans (both Radical

and moderate) on one side, and on the other Johnson and his allies in

the Democratic party in the North, and the conservative groupings in

the South. The decisive battle was the election

of 1866. Johnson campaigned vigorously but was widely ridiculed.

The Republicans won by a landslide (the Southern states were not

allowed to vote), and took full control of Reconstruction. Johnson was

almost powerless.

Photo is of the Johnson family plot containing President Johnson and his wife Eliza atop Signal Hill in 1875. Known today as Monument Hill. Also here are his two unmarried sons Charles and Robert.

The

Republicans were determined to rid themselves of Johnson. There were

two attempts to remove President Andrew Johnson from office. The first

occurred in the fall of 1867, after a furious

debate, a formal vote was held in the House of Representatives which

failed 108-57.

Later,

Johnson notified Congress that he had removed Edwin

Stanton as Secretary of War (Johnson had wanted to replace

Stanton with former General Ulysses S. Grant who refused to accept the

position). This violated the Tenure of Office Act, a law enacted by

Congress in March 1867 over Johnson's veto, specifically designed to

protect Stanton.

Johnson had vetoed the act, claiming it was unconstitutional (years

later in the case Myers v. United States in 1926, the Supreme

Court ruled that such laws were indeed unconstitutional).

The

House impeached Johnson for intentionally violating the Tenure of

Office Act. On March 5, 1868, a court of impeachment was constituted in

the Senate to hear charges against the President. William M. Evarts

served as his counsel. Eleven articles were set out in the resolution,

and the trial before the Senate lasted almost three months. Johnson's

defense was based on a clause in the Tenure of Office Act stating that

the then-current secretaries would hold their posts throughout the term

of the President who appointed them. Since Lincoln had appointed

Stanton, it was claimed, the applicability of the act had already run

its course. In May, 35 Senators voted "guilty" and 19 "not guilty." As

the

Constitution requires a two-thirds majority for conviction in

impeachment trials, Johnson was acquitted. A single changed vote would

have sufficed to return a "Guilty" verdict. Seven Republican senators

were disturbed  by how the proceedings had been manipulated in

order to

give a one-sided presentation of the evidence. Senators William Pitt Fessenden (Maine), Joseph S.

Fowler (Tennessee), James W. Grimes (Iowa), John B. Henderson

(Missouri), Lyman Trumbull (Illinois), Peter G. Van Winkle (West

Virginia) and Edmund G. Ross (Kansas), who provided the decisive vote,

defied their party and public opinion and voted against conviction.

by how the proceedings had been manipulated in

order to

give a one-sided presentation of the evidence. Senators William Pitt Fessenden (Maine), Joseph S.

Fowler (Tennessee), James W. Grimes (Iowa), John B. Henderson

(Missouri), Lyman Trumbull (Illinois), Peter G. Van Winkle (West

Virginia) and Edmund G. Ross (Kansas), who provided the decisive vote,

defied their party and public opinion and voted against conviction.

Had

Johnson been successfully removed from office, he would have been

replaced with Radical Republican Benjamin Wade,

making the presidency and Congress somewhat uniform in ideology,

although in many ways Wade was more "radical" than the Republicans in

Congress. This would have established a precedent that a President

could be removed not for "high crimes and misdemeanors," but for purely

political differences.

Here is a photo of me in front of Johnson's grave that my wife Debbie took. Family tradition holds that Johnson chose this spot as his final resting place, and it has a commanding view of the distant mountains. The words inscribed there are a testament to Johnson's political legacy - "His Faith in the People Never Wavered."

One of

Johnson's last significant acts was granting unconditional

amnesty to all Confederates on Christmas Day, December 25, 1868. This

was after the election of U.S. Grant to succeed him, but before Grant

took office in March 1869.

Johnson was an unsuccessful candidate for election to the United States Senate from Tennessee in 1868 and to the House of Representatives in 1872. However, in 1874 the Tennessee legislature did elect him to the U.S. Senate. Johnson served from March 4, 1875 until his death. He is the only former President to serve in the Senate. In his first speech since returning to the Senate, which was also his last, Johnson denounced the corruptions of the Grant Administration. His passion aroused a standing ovation from many of his fellow senators who had once voted to remove him from the presidency.

On July

28, 1875, Johnson and his wife were visiting their daughter at her home

near Elizabethton, Tennessee when he suffered a stroke. He recovered

somewhat but suffered a second stroke the next day. He passed away two

days later. He was returned to Greeneville where his body lay in state

at the Greeneville County Courthouse (only a couple of blocks from his

home). Because of the hot weather, his body started to decompose so the

casket remained closed. On August 3, his body was escorted by honor

guard to his gravesite where a simple Masonic funeral service was

held. He was buried covered in the American flag and with his head

resting on a copy of the U.S. Constitution. The gravesite was on land

he owned and had personally chosen for his burial. His wife Eliza died

six months later and was buried along side him. The family erected the

tall obelisk over Andrew and Eliza Johnson’s

grave in 1878. There was a dedication ceremony, and afterwards, this

became known as “Monument Hill.” The

photo here is of the eagle atop Johnson grave.

Johnson's

personal life was sad. His wife Eliza became an invalid. She supported

her husband in his political career, but had tried to avoid public

appearances. Though she lived in the White House, she was not able to

serve as First Lady due to her poor health. He had three sons, Charles,

Robert and Andrew Jr. (nicknamed Frank) and two daughters, Martha and

Mary. Charles, a surgeon during the Civil War, fell from a horse and

died in 1863 at the age of 33. Robert, who became a colonel and the

commander of the 1st Tennessee Cavalry (a pro-Union Tennessee regiment)

during the war, never got over the death of his brother and resigned

his commission shortly afterwards. He committed suicide at the age of

36 in the Johnson home shortly after the family’s return from

Washington in 1869. Both brothers Charles and Robert, who had severe

alcoholic problems, are buried side by side near their parents. Andrew

Johnson Jr. was the youngest of the Johnson children by 18 years

and the only son to marry. He never had children and died four years

after his parents. Martha, who was the oldest of the children and her

father's favorite, served as White House hostess for her

invalid

mother. Martha’s husband, David Trotter Patterson, had been one of

Tennessee’s Senator at the time of Johnson’s impeachment. Patterson

cast one of the Democratic “not guilty” votes during the trial.

Martha lost both David and their daughter Belle within months of

each other in 1891. Martha, however, lived longer than any of the other

Johnson children. She witnessed the turn of a century, and died in

1901. Mary and her first

husband, Daniel Stover, had three children, Sarah, Lillie and Andrew.

Daniel died during the

Civil War and the widowed Mary moved to the White House with her

parents. She preceded the family's return to Greeneville to renovate

and restore the family home to accommodate her and her children.

However, a short time after finishing she married William Brown and

moved away (they divorced after the deaths of her parents).

Johnson's

personal life was sad. His wife Eliza became an invalid. She supported

her husband in his political career, but had tried to avoid public

appearances. Though she lived in the White House, she was not able to

serve as First Lady due to her poor health. He had three sons, Charles,

Robert and Andrew Jr. (nicknamed Frank) and two daughters, Martha and

Mary. Charles, a surgeon during the Civil War, fell from a horse and

died in 1863 at the age of 33. Robert, who became a colonel and the

commander of the 1st Tennessee Cavalry (a pro-Union Tennessee regiment)

during the war, never got over the death of his brother and resigned

his commission shortly afterwards. He committed suicide at the age of

36 in the Johnson home shortly after the family’s return from

Washington in 1869. Both brothers Charles and Robert, who had severe

alcoholic problems, are buried side by side near their parents. Andrew

Johnson Jr. was the youngest of the Johnson children by 18 years

and the only son to marry. He never had children and died four years

after his parents. Martha, who was the oldest of the children and her

father's favorite, served as White House hostess for her

invalid

mother. Martha’s husband, David Trotter Patterson, had been one of

Tennessee’s Senator at the time of Johnson’s impeachment. Patterson

cast one of the Democratic “not guilty” votes during the trial.

Martha lost both David and their daughter Belle within months of

each other in 1891. Martha, however, lived longer than any of the other

Johnson children. She witnessed the turn of a century, and died in

1901. Mary and her first

husband, Daniel Stover, had three children, Sarah, Lillie and Andrew.

Daniel died during the

Civil War and the widowed Mary moved to the White House with her

parents. She preceded the family's return to Greeneville to renovate

and restore the family home to accommodate her and her children.

However, a short time after finishing she married William Brown and

moved away (they divorced after the deaths of her parents).The cemetery was owned by the family until 1906. From 1906 until 1942, the cemetery was under the jurisdiction of the War Department. The first veteran burial took place in 1908, one hundred years after the birth of Andrew Johnson. By 1939, there were 100 graves. When the National Parks Service took over in 1942, their original policy was to allow no more burials. The DAR and American Legion, however, began lobbying for the reactivation of the Cemetery, and in 1946 they found success. The cemetery is still active today. This is one of the few cemeteries administered by the National Park Service to have soldiers other than those who fought in the Civil War. Here you will find veterans from the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the Gulf Wars.

Here are some webpages of interest:

A secondary NPS site on the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site

White House Biography of Andrew Johnson

The Internet Public Library Biography

The American President Biography

Mr. Lincoln's White House: Andrew Johnson

Johnson's obituary from the New York Times

Andrew Johnson's 200th Birthday Celebration site at DiscoverGreeneville.com

|

|

|

|